Swamp in the City: Cajun Music Night

Swamp in the City: Cajun Music Night

Two-step the night away to the sounds of Cedric Watson & Bijou Creole at 7pm and stay for the Daiquiri Queens in a return performance at 9pm.

Two-step the night away to the sounds of Cedric Watson & Bijou Creole at 7pm and stay for the Daiquiri Queens in a return performance at 9pm.

Free drum performance on the barge from New York is the premier all-women, Black-led, percussion ensemble

Red Hook was one of the earliest areas in Brooklyn to be settled. The Dutch established the village of Roode Hoek (Red Point) in 1636. The area is said to have been named for its red clay soil and “point” refers to its narrow upland peninsula surrounded by tidal marshes projecting into the harbor.

A map from the 1760s shows a developed village at a time when there was little else in Brooklyn. In the 1840s the Atlantic Basin opened and Red Hook became one of the busiest ports in the country and a major destination for Erie canal boats, which delivered their grain and over-wintered in Erie Basin, where IKEA is located today.

Red Hook has long had a reputation as a tough section of Brooklyn. The 1990 Census estimated the population at just fewer than 11,000 with more than a third under age 18. That same year the average income per household was under $10,000. Unemployment in Red Hook was estimated at 30 percent among men and 25 percent among women. These challenging conditions have been part of the neighborhood for a long time. Al Capone got his start as a small-time criminal here, along with the wound that led to his nickname, “Scarface.” During the Great Depression, public housing replaced much of the dilapidated dock worker housing (among the oldest row houses in Brooklyn outside Brooklyn heights). The Red Hook Houses, built in 1938, were originally built for families of dock workers and were one of the first and largest Federal Housing projects in the country. In 1950, at the peak of the longshoreman era 21,000 people lived in the neighborhood. Today Red Hook’s East and West Houses are home to the great majority of the neighborhood: an estimated 8,000 people, or 73 percent of Red Hook’s total population.

After the peak of the 1950s, Red Hook suffered a loss of jobs, population and geographical isolation. The 1946 opening of the Gowanus Expressway and the 1950 opening of the Brooklyn Battery Tunnel cut the neighborhood off from the rest of the borough. Over the next decade or so, the area bled jobs as shipping underwent a dramatic change. Freight lines began moving goods in shipping containers, rather than the traditional break-bulk shipping of sacks, barrels, and crates, which were gathered into large nets or slings of rope and hoisted out of a ship’s hold. Containerized shipping required greater upland space than was available in Brooklyn and fewer hands to load and unload. The waterfront jobs moved to New Jersey, and the economy of the neighborhood changed drastically.

In June 1994 the neighborhood and community board released its “197-a plan,” a document submitted to the city pointing the way for a waterfront revival. According to the “197-a”, in 1972 the city approved an urban renewal plan to develop 230 acres of waterfront for a modern container port, waterfront park and 225 units of housing for those who would be displaced by the container port. The proposal, according to the plan, “put a cloud of condemnation over many residential blocks which were eventually not taken due to changes in the internal container port design. This led to further decline and abandonment of housing.”

The city and the Port Authority of New York & New Jersey has a troubled history in Red Hook. According to one local tour guide, “The Port Authority has divested itself of several hundred acres with little or no long-term planning.” Gov. Mario Cuomo’s campaign literature in 1994 touted Red Hook’s Fish Port as a $27 million investment in the neighborhood that created 700 jobs. What the ad neglected to mention was that the Fish Port had closed well before the literature was distributed, just six months after it opened. That local tour guide and others estimated that the fish port cost $42 million to build including leasing fees and other expenses. In 1993 the Port Authority sold the property for $2 million to Erie Marine Associates. They then rented a portion of the property to the city, which redeveloped the waterfront into an evidence impound lot. “The most stunning views on the Harbor are commanded by broken-down cars,” A cheerful green-and-white Fish Port logo remained at Bay and Columbia street well into the 21st Century as a reminder of the failed project.

To their credit, the police department, as part of the sale agreements, built the Columbia Street Pier, a public esplanade that extends out into Gowanus Bay. The agency also agreed to pay $50,000 toward the annual maintenance of the Firefighter Louis Valentino Pier and Park at the end of Coffey Street.

The Valentino Pier, completed in 1996 by the New York City Economic Development Corporation after much wrangling and pressure from the neighborhood, commands one of the best views of New York Harbor and the Statue of Liberty in the city. It became a city park in 1999.

In another transaction, the Port Authority sold developer Greg O’Connell 28 acres, 10 of them on the waterfront, for the bargain price of $500,000 in 1992. O’Connell redeveloped the Beard Street Pier into space for small manufacturing and has helped bring several businesses into the neighborhood and built a half-mile of waterfront public esplanade.

This first phase of the public waterfront access plan was constructed as an open pier where O’Connell has hosted the annual Red Hook waterfront arts festival, the Young People’s Performance Festival and the Brooklyn Waterfront Artists Coalition exhibits. Red Hook was also home to the largest concentration of Civil War-era warehouses in the city but in an act that angered the local community, UPS tore down nearly all of the Lidgerwood Factory Warehouse next to Valentino Park. They did this over Memorial Day weekend in 2019, in the face of community resistance, before completely abandoning the site. About two weeks later, the S.W. Bowne warehouse, at the mouth of the Gowanus Canal endured a significant and suspicious fire after a period of aggressive neglect. This led to the final demolition of this last remaining infrastructure in NYC directly relating to the towpath era of the Erie Canal. The New York State Barge Canal Grain Terminal, built in 1922 off Halleck Street to receive grain shipments coming through the Erie Canal, remains standing as of 2022, a century after it began operation.

O’Connell’s Beard Street Pier was once home to the Trolley Museum. Red Hook resident Bob Diamond started the small museum in the 1990s with the intention of linking the neighborhood to Carroll Gardens with trolleys once again. He received $210,000 through the federal Intermodal Surface Transportation Equity Act (ISTEA), in 1996, and started constructing the project but he experienced financial troubles. A NYC Department of Transportation study funded by a $300,000 federal grant, concluded that the streets in the neighborhood were too narrow for the wide turns streetcars would need to make. Following Hurricane Sandy, several of Diamond’s trolleys were donated to the Shoreline Trolley Museum in East Haven, CT.

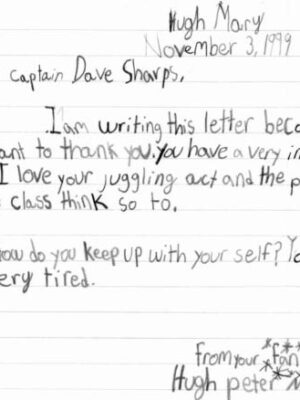

From 1994 until the arrival of a multitude of art venues and restaurants, the main neighborhood attraction in this part of Red Hook was the Waterfront Museum, located in the Lehigh Valley Barge No. 79.. The wooden covered cargo barge is the only surviving example of its kind and is anchored at Pier 44 off Conover Street. The museum has sponsored educational programs, circus acts and a sunset music series. It is available for rental and hosts a variety of events, and it has some of the best sunsets and waterfront views in the city.

For more on Red Hook and New York Harbor, check out Red Hook WaterStories, a great history project by our friends at Portside New York.

The Lehigh Valley No. 79 is an all-wooden barge built for the Lehigh Valley Railroad in 1914 to shuttle cargo between boxcars in New Jersey and ships and piers all around the Port of New York. Such barges are known as lighters. Traditionally, lighters are small vessels that shuttle cargo between ships at anchor and shore. The name “lighter” comes from this lightening of the load to get it into shallow water by taking it in small portions. In the archipelago of New York Harbor, lighters sometimes moved cargo between shore and ships at anchor (and still do today), but more often they moved cargo between ship piers on one side of the harbor and railroad piers on another side. The period in which lighters moved most of New York’s cargo in this way is known as the Lighterage Era, which extended roughly from 1840 – 1970.

From the opening of the Holland Tunnel in 1927 to that of the Verrazano Narrows Bridge in 1964, roadways increasingly connected Brooklyn and Manhattan to New Jersey. Shipping containers were first introduced to the Port of New York and New Jersey in 1956 and steadily moved shipping activity to New Jersey over the next thirty years. The railroads collapsed in the late 1960s, and by 1987 breakbulk (non-containerized) shipping and the need for lighterage was all but eliminated in the harbor.

We’re not certain when the Lehigh Valley No. 79 stopped moving freight. The Lehigh Valley Railroad sold the barge to prominent stevedoring company William Spencer & Son in the 1940s. The barge continued to handle freight at least into the 1970s before it was sold to a pile driving company operated by Harry Shellhorn, which let it become a non-floating storage barge on the tideflats at Edgewater, NJ.

David Sharps bought the barge in 1985. David got his start as a juggler on Carnival Cruise Lines’s first ship, the Mardi Gras. He and his partner performed on ships in the Caribbean, Aegean, and Mediterranean, then went to Paris to attend the performance school Ecole Internationale De Theatre Jacques Lecoq where David lived aboard a boat on the Seine. When they graduated, David and his juggling partner came to New York City to put their training to work as Serious Foolishness. David saw the barge as a way to have his own performance space.

Together, with a group of tug and barge dwellers centered in Lighthouse Boat Basin on the Jersey side of the harbor, David Sharps founded the Hudson Waterfront Museum and the group elected him founding president. Largely at his own expense, along with volunteers and donated materials, David floated and restored the barge, successfully applied for its addition to the National Register of Historic Places (with the help of Norman Brouwer, then curator of ships at South Street South Street Seaport) and developed a base of funding for free programs open to the general public.

Once afloat, the Hudson Waterfront Museum’s barge moored at Hoboken’s Erie-Lackawanna terminal plaza for the summer of 1989 as part of Hoboken’s waterfront festival from June 4 – August 27. Over a thousand visitors came aboard the barge the first day it opened, paying a dollar a piece. David thought he had it made. After the festival, people didn’t come to the waterfront. The summer programming included a series of history events that drew the same few dozen people, but it ended with entertainment that packed the house.

The Ball Machine

With the showboat barge taking shape, David turned his attention to his performance. For his final project at performance school in Paris, David had created a piece around a sort of Rube Goldberg-style contraption, but the machine barely held together for the performance. He wanted to build on that production at the showboat and doing so would require a more professional structure. He applied for grant funding and commissioned sculptor George Rhoads to build a machine to meet his needs.

Rhoads had been experimenting with audio kinetic sculptures since the 1950s and came to prominence with television appearances in the 1970s and a 1981 commission for the Port Authority Bus Terminal in Manhattan, The 42nd Street Ballroom. David saw the Port Authority Ball machine and was so taken with it that he sought out George Rhoads.

After discussing David’s vision, Rhoads and his team of metal workers in Ithaca, NY produced the audiokinetic sculpture or ball machine that mesmerizes and delights Waterfront Museum visitors (except when it’s taken off display for special events).

Fighting the Tides in Hoboken

Back in Hoboken, the festival’s success sparked a vision for turning the old Erie Lackawanna Ferry Terminal into an arts center with performance and art exhibits on the second floor. Response to this vision was enthusiastic. The Hoboken Waterfront Museum plan for the ferry terminal sailed through layers of bureaucracy, winning approval at every turn. New Jersey Transit had vacated its offices in that part of the building. David was invited to demolish the office partitions and take the studs for his trouble. The studs replaced the worn out floors under the barge’s roof hatches. Meanwhile, David continued to operate the museum and showboat until New Jersey Transit expressed concern about letting the barge moor there permanently. Suddenly, the barge was evicted.

About that time, Liberty State Park was taking shape. The people organizing the park knew that the Lehigh Valley Railroad had operated Morris Basin at the northeast corner of the park and invited David to take the barge there for a residency, promoting it in their visitors center as part of the Central Railroad of New Jersey terminal’s 150th anniversary celebration. The barge stayed for the winter, but the Lehigh Valley No. 79’s original, freight handling homeport would only be a temporary moorage for the museum.

With a private developer coming in to build out the marina, this former Lehigh Valley Railroad terminal wouldn’t be the museum’s permanent home. The barge returned to Hoboken in the summer, then went up river to the end of the long dock in Piermont. The next year the barge spent October doing performances at South Street Seaport Museum before returning to the mudflats in Edgewater from late fall 1991 into winter 1992-1993 to fix some leaks, settling this time by the barges of the Manhattan Island Yacht Club, just south of Ronnie Ingold’s property. David, the new museum, and its old barge still needed a permanent place to moor that was accessible to visitors.

Pete Seeger Clears a Channel

In the early 1990s, folk singer and Hudson River activist Pete Seeger organized a meeting of maritime heritage organizations aboard a historic ship at South Street Seaport to discuss ways to repeat the success he’d had with his replica Hudson River Sloop Clearwater in building excitement around the river. David, sitting next to Pete, was the last to speak as they went around the circle. He told the story of the barge and the museum and said he was about ready to give up if he couldn’t find a place where he could moor the barge and live aboard.

Pete said “Well, this is what we’re talking about. How can we help David out?” Historian Michael Mann and some others said “go to Brooklyn.”

This led to a meeting with Anthony Manheim, who was putting together Brooklyn Bridge Park, but Manheim thought the park would be years in the making, and David needed a solution right away. Others put him in touch with Carroll Gardens figure Buddy Scotto, who said David should talk to Greg O’Connell.

Greg was a former school teacher and police officer with a passion for real estate, buying his first house with some college buddies while they were still in school together. As a cop he was the arresting officer when Philipe Petit walked a tightrope between the twin towers of the World Trade Center.

Greg had purchased a set of Civil War era warehouses in Red Hook from the Port Authority. The site adjoined Erie Basin with its Revere Sugar Refinery and Todd Shipyard and included a grain elevator and warehouses that had stored cotton during transhipment from Southern coastal schooners and square riggers and other ships taking the cotton on to processing mills, key commodities in New York Harbor’s economy.

Part of Greg’s agreement in purchasing the properties was that he had to develop a publicly accessible waterfront. The Waterfront Museum barge would get people afloat and its programs would attract people to a remote neighborhood at the foot of Wall Street’s skyscrapers.

Greg liked the idea but said David should talk to the borough president and the community board; if they were on board then he would be too. Marilyn Gelber, who was working for Borough President Howard Golden, thought it was a great idea and that Greg would be an ideal partner. It was decided that Red Hook would be home for the barge beginning in 1994. Moving to Brooklyn meant the barge had to reapply to the National Register of Historic Places after moving location across state lines, and a name change was in order. The Hudson part was dropped. From now on the showboat barge would be known as The Waterfront Museum.

A Red Barge in Red Hook

Captain Dick Foster, who had been a friend to David and the Lehigh Valley No. 79 almost from the first bucket of mud David scooped out of the hold, had offered to tow the barge to its new home, but he was running late.

A friendly government vessel with a shallow draft pulled the barge into the river where Captain Dick could pick it up, but before he could get his tug from Jersey City to Edgewater, duty called and the government vessel had to go on its way. They set the barge adrift to wait for Captain Dick’s arrival. Forty-five minutes later, Captain Dick caught up with David and his barge just upstream from the George Washington Bridge.

The band that had planned to play for the barge’s arrival had gone home long ago and the balloons had wilted by the time the Lehigh Valley No. 79 arrived at Pier 45 and began the work of making this neighborhood home.

With moorage secured, David and his wife Sarah could move aboard with their two daughters. The barge did its part to draw people to Red Hook’s waterfront with Circus Sundays and Sunset Concerts on summer Fridays along with school trips where kids got to touch history and feel the harbor wash against the barge, helping them appreciate that they live on a group of islands in the midst of a fragile and fertile estuary. The Waterfront Museum helped Red Hook residents rediscover their waterfront at a low point in the community’s history.

After a peak in the 1950s, Red Hook suffered a loss of jobs, population and geographical isolation. The Gowanus Expressway and the Brooklyn Battery Tunnel cut the neighborhood off from the rest of the borough. The area bled jobs as waterfront work moved to New Jersey, and an abortive plan to move the Fulton Fish Market to the waterfront left a swath of empty buildings in its wake.

Revival

Change was afoot. By 2000 Red Hook’s revival was well underway and enough people came by that the Waterfront Museum began having regular Open Hours on Thursdays and Saturdays. Then in September 2001, David and his family watched the plume of smoke and ash rise from the World Trade Center, just over the top of the Liberty Warehouse northeast of Pier 44. For many the city seemed to teeter on a precipice, but Red Hook was not about to turn back. The barge also had more struggles that it too would overcome.

By 2002 it was clear that the barge was taking on water at an unsustainable rate. The New York State Canal Corporation made its Repair Facility in Waterford available to the Waterfront Museum. Tugs towed the Lehigh Valley No. 79 the long journey of 150 miles up the Hudson and the barge came out of the water in dry dock for over 100 days. All the work was carefully documented in written reports and photographs.

The museum spent $280,000 on labor and lumber. $20,000 worth of lumber replaced the entire bottom, the bow and stern below the water line, and a little above, and selected planks on the sides. The team sistered some longitudinal frames where the scarf joints were weakening. David had sheathed the sides in felt paper copper back on the mudflats. Now he sheathed it in plastic.

This sheathing was vital to maintaining an all-wood barge in New York Harbor. For about a century, wood structures in New York Harbor were pretty resilient and lasted as long as they didn’t suffer too much strain from collisions and abrasion or fire. All this began to change in 1972 when Congress passed the clean water act and New York City took more concerted action toward reducing the amount of raw sewage in the harbor. About 20 years after passage of the Clean Water Act wooden piers and other wood structures in the harbor began to degrade and collapse at a higher rate. This was because the harbor was returning to life with populations of aquatic organisms on the rise, including our local shipworms who feed on wood.

Unfortunately, Pier 45 wasn’t sheathed in plastic. When David and his daughters visited Brooklyn one summer day during the barge’s haul-out they found that the old pier had collapsed. When they brought the barge back to Brooklyn, David and his family had to moor on Columbia Street where John Quadrozzi made space available for them while a new pier and its mooring structures were built. Work on the new pier finished in 2005 and the barge finally arrived at its most permanent moorage since the Edgewater mudflats.

The Waterfront Museum resumed operations with school trips, performances, and Open Hours. Then IKEA bought Erie Basin’s Todd Shipyard for its first location in NYC and the Waterfront Museum joined a hard-fought but ultimately unsuccessful battle to save the massive and invaluable graving docks and the old brick entrance through which so much of Red Hook’s maritime industrial history had passed.

The museum launched its first website in 2011 and weathered the ferocious Hurricane Irene. Then came Sandy and at age 98 the Lehigh Valley No. 79 faced one of the gravest threats it had seen since the advent of containerization.

Hurricane Sandy

The forecast for October 29, 2012 convinced David’s family to move ashore. He took up the watch on the barge with two volunteers. Brooklyn sheltered the barge from the worst of the winds, but those winds also kept the tide from going out. So when the second (especially large) high tide of the storm came in, it piled on top of the first, a full 12’ above the low water mark. As the waters rose, David and his crew set lines to cleats on the Brooklyn side of the embayment between Pier 44 and the remnants of the collapsed Pier 45 and eased the lines, trying to keep the barge in the middle. Then, as the waters finally receded, they hauled the lines in, all the while fighting the wind to keep the boat off the timber clusters the barge normally moors against. The center piling rises higher than the two main clusters and helped keep the barge from blowing into the catwalks but the hull briefly hung up on one wooden bracing, compromising the plastic sheathing that keeps the marine borers at bay. The only other damage the barge sustained was the loss of the skylights over the roof cargo hatches.he emotional strain of the fight to save his home and life’s work, and then living in a community devastated by the flood, took a toll, but David joined the rest of Red Hook in cleaning up their community. The barge and the community proved their resilience, and the Waterfront Museum set about preparing for the barge’s centennial celebration. The featured event was a performance all about the barge, its history, and the stories of the people who lived and worked on it and other, similar, barges.

But Hurricane Sandy wasn’t done with the barge quite yet. Disaster relief helped pay for a second haul-out that the Coast Guard required in 2015. The work this time was far less extensive than in 2002. David and the team of shipwrights replaced one bottom plank that had been destroyed by dry rot. They conducted repairs and reinforcement to the four corners. The barge headed back to Brooklyn in September, pausing in Waterford where it was the Belle of the Ball at the annual Tugboat Roundup.

Then it was back to business with art exhibits, performances, and school trips. In 2017, the barge hosted an event kicking off the 8 year celebration of the Erie Canal’s bicentennial, marking the start of the canal’s construction in 1817. Exciting plans came together for an American premiere of an Arthur Miller script about Red Hook and the longshoremen who worked on barges like the Lehigh Valley No. 79. Opening night for this stage adaptation of Arthur Miller’s unproduced screenplay “The Hook” was set for June of 2020.

After closing for 18 months, the museum slowly reopened to the public as the Covid-19 pandemic waned. The show did go on, but not until June of 2023 when “The Hook” saw packed houses and rave reviews, returning the barge to life for a few more years before the next scheduled visit to the dry dock in 2025.

The Lehigh Valley No. 79 is an all-wooden barge built for the Lehigh Valley Railroad in 1914 to shuttle cargo between boxcars in New Jersey and ships and piers all around the Port of New York. Such barges are known as lighters. Traditionally, lighters are small vessels that shuttle cargo between ships at anchor and shore. The name “lighter” comes from this lightening of the load to get it into shallow water by taking it in small portions. In the archipelago of New York Harbor, lighters sometimes moved cargo between shore and ships at anchor (and still do today), but more often they moved cargo between ship piers on one side of the harbor and railroad piers on another side. The period in which lighters moved most of New York’s cargo in this way is known as the Lighterage Era, which extended roughly from 1840 – 1970. The Lehigh Valley Railroad sold our lighter, the Lehigh Valley No. 79, to stevedoring company William Spencer & Son in the 1940s. A pile driving company operated by Harry Shellhorn was the last to use the No. 79 for industrial operations, letting it become a non-floating storage barge on the tideflats at Edgewater, NJ. There, David Sharps acquired it in 1985 and began its restoration into a cultural center now called the Waterfront Museum.

Until the advent of containerized shipping in 1956, nearly all of the ships carrying international cargo into or out of New York docked in Brooklyn and Manhattan, but nearly all the railroads that connected the Port of New York to the states west of the Hudson ended on the New Jersey side of the harbor. To connect ships to trains, the railroads developed a massive fleet of lighters, including the Lehigh Valley No. 79.

Our lighter was built for and operated by the Lehigh Valley Railroad, which ran from Buffalo, NY to Jersey City via Pennsylvania’s anthracite coal region and the Lehigh Valley (Allentown, Bethlehem, and Easton, PA). This barge shuttled cargo across the harbor that traveled the rails in boxcars. This included cargo shipped in small and medium sized crates, barrels, and sacks, as well moderate sized unpackaged cargo, like hides. This is known as break bulk cargo. Oversize cargo, such as large machinery and weather-resistant goods like I-beams and pig iron or other processed metals, were also considered break bulk but shipped on flat deck lighters. Bulk cargo (loose coal, grain, ore, etc) crossed the harbor in deep hopper barges or on shallow stone scows.

Nearly every lighter in New York Harbor had a captain. These barges had no engines and could not be steered or moved without a tugboat. The captain provided security, ensured cargos reached the correct destinations, and conducted routine maintenance on the lighter and its mooring lines. Barge captains lived aboard and most had families. On many covered lighters, the captain and his family lived in a cabin on the roof. In 1930, the captain of the Lehigh Valley No. 79 was William Baird, who lived in a cabin on the roof with his wife Christine.

Posts inside the cargo area supported the cabin on the roof but left little room to operate forklifts, so as that technology became more common in the middle of the 20th century, the cabin was removed from the roof so the posts could be removed. From then on, most families lived on shore and the captains with families worked shifts of a week or two. Some barges retained permanent captains who were single or married but without children.

From the opening of the Holland Tunnel in 1927 to that of the Verrazano Narrows Bridge in 1964, roadways increasingly connected Brooklyn and Manhattan to New Jersey. Shipping containers were first introduced to the Port of New York and New Jersey in 1956 and steadily moved shipping activity to New Jersey over the next thirty years. The railroads collapsed in the late 60s, and by 1987 breakbulk shipping and the need for lighterage was all but eliminated in the harbor.

Today, the Lehigh Valley No. 79 is the only surviving all-wooden barge from New York Harbor’s lighterage era.

Lilac: steam-powered lighthouse tender operated by the Lilac Preservation Project

Mary A. Whalen: 1938 oil tanker operated by Portside New York

John A. Noble’s floating studio: barge based artist’s studio preserved at Snug Harbor cultural center by the Noble Maritime Collection

W.O. Decker: last wooden tugboat in New York harbor, South Street Seaport Museum

Schooner Pioneer: sand schooner, South Street Seaport Museum

Wavertree: cargo square rigger, South Street Seaport Museum

Ambrose: lightship, South Street Seaport Museum